Terrence Malick’s radical editing strategy

You remember your life like a Terrence Malick film:

A series of disjointed jump cuts of half-remembered images.

Starting with Tree of Life, Malick radically changed how he structures and edits his films. Discarding traditional narrative tools such as continuity editing, dialogues, and traditional flashbacks, he organized his films to mirror fleeting fragments of memories. To achieve this, Malick collaborated with five editors on Tree of Life, giving them each the flexibility to experiment:

“Terry is willing to try anything, absolutely anything,” says Weber. “Sometimes we’d cut a character out of a scene, or cut all the dialogue out of a scene, just to see if it worked. And when you’ve worked with him for any length of time, you can even try that without asking him about it first. He’s very open to looking at anything that you try.” That flexibility reaches even to the way Malick likes to give direction: “Terry isn’t the kind of guy who would ever give a direction like, ‘Cut ten frames from this shot.’ He’d rather say something like, ‘Make this scene feel more like a fleeting thought.’”

– excerpt from “Growing The Tree of Life: Editing Malick’s Odyssey” by Bilge Ebiri

The opening of To the Wonder – perhaps the most sublime 20-minutes Malick ever directed – captures how you would remember an exotic trip you took years ago: elliptical cuts that mirror the gaps in your memories; silent images; whispered dialogues.

While many bemoan – incorrectly – that late Malick films are obtuse, they are in some ways much more intuitive in their structure than traditional films.

Sympathy for a henchmen

Serialized between 1994 and 2000, The Invisibles chronicles the adventures of The Invisible College, a secret cell of resistance fighters battling the Archons of the Outer Church, inter-dimensional alien gods who have already enslaved most of the human race without their knowledge. While the basic premise of the series is similar to those of the late 90’s SF films such as The Matrix and Dark City, The Invisibles is more eclectic and metaphysical in its scope. Morrison used the series as a platform to explore the various ideas and genres that interested him: Buddhist philosophy, conspiracy theories, pop culture, obscure literature, mythology, art.

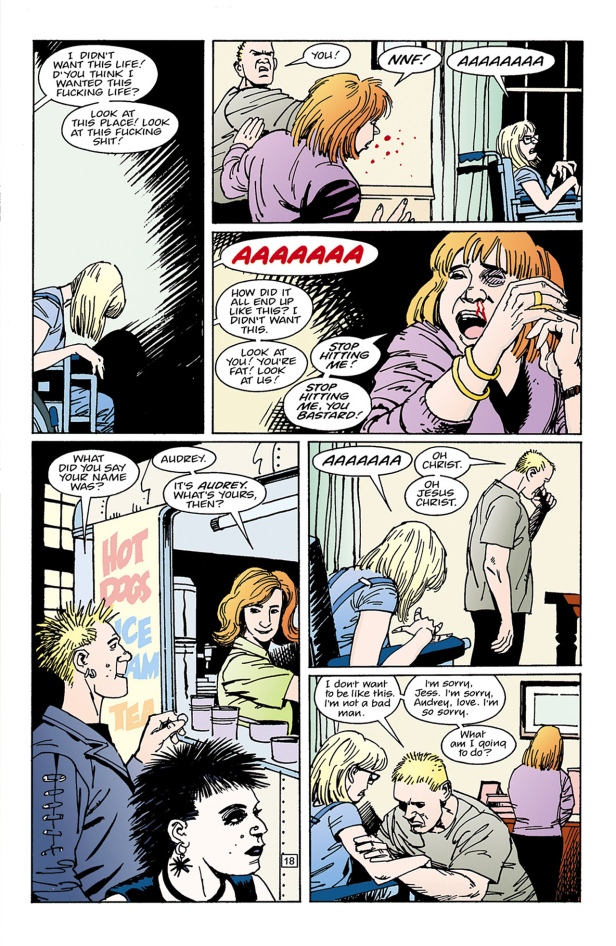

Best Man Fall (script: Grant Morrison, art: Steve Parkhouse) is a standalone issue that explores the life and death of Bobby Murray whose connection to The Invisibles universe is unclear for the most of the issue. Unlike other issues that have a SF or fantasy bent, the issue is tonally closer to an indie autobiographical comics, which makes the reveal at the end all the more shocking.

In The Invisibles issue #1, King Mob (a Morpheus-like cell leader) breaks into a juvenile correction center ran by the Archons of the Outer Church to rescue Dane. (a Neo-like protagonist) It’s an unambiguously heroic action sequence that establishes King Mob as a charismatic resistance fighter.

Around the end of Best Man Falls, it is revealed that Bobby Murray was one of the nameless henchmen killed by King Mob during the issue #1 break-in. Best Man Falls builds-up Bobby as a nuanced character, highlighting the cost of violence. What was once a thrilling rescue mission reminiscent of The Matrix lobby shootout becomes a tragedy with irreversible consequences.

Issue #1 rescue sequence: Bobby is the henchman who is shot in the face

Best Man Fall is the best single issue of graphical fiction that I’ve ever read and the most emotionally powerful issue that Morrison has ever written. Using a quasi-rashomon structure based twist to highlight a central theme could have easily been gimmicky and manipulative. Just look at how hollow Sicario, which had an identical sub-plot involving one of the henchmen, was. Rather, the power of Best Man Fall comes from its editing strategy which is similar to Malick’s approach in his post Tree of Life films.

As I lay dying…

Best Man Fall is structured as a series of non-linear flashbacks, highlighting key moments in Bobby’s life. In visual storytelling, flashbacks are mostly used to establish causal relationship:

- Causal relationship in plot developments: event A that occurred in the past caused event B occurring in the present

- Causal relationship in character developments: event A that occurred in the past informs the behavior of character A in the present

However, flashbacks in Best Man Fall doesn’t establish any causal relationship. Just like late Malick films, the flashbacks are edited to mirror memories, specifically memories of a dying man.

Looking at the opening 4-pages of the issue:

- Match cuts: Morrison and Parkhouse use two match cuts (child Bobby running -> adult Bobby falling, bomb explosion -> fireworks) in the pages. The cuts are designed to capture how a specific image triggers a half-forgotten memory. The use of match cuts in the initial pages ease the readers in.

- Lack of establishing shots and signifiers: just like Malick films, there are no explicit signifiers (captions, color tones) indicating temporal relationships among scenes. The issue also forgoes continuity editing, almost entirely devoid of establishing wide-shots. This makes the issue slightly disorienting, just as our memories can be slightly disorienting.

- Execution: employing a clever editing strategy only gets you so far. The issue works because its innovative structure is accompanied by flawless execution. It works because Morrison can write heart achingly beautiful lines like “It’s not lost. I’m letting it play with the fireworks.” It works because Parkhouse is so good at portraying emotional nuances with subtle facial expressions.

As the issue converges to the moment of Bobby’s death, the cuts become more jagged, capturing how Bobby’s memory is becoming more erratic.

Eventually, the issue intercuts Bobby’s ugliest (domestic abuse), proudest (overcoming his childhood fear), and happiest memories. (marriage proposal) – sharp tonal contrasts of the events perfectly encapsulates the story’s central theme.

Bobby is not a superficial narrative construct with character traits that can be neatly decoded by Rosetta stone moments in his life. He is a complex human being who experienced joy, fear, resentment, disappointment, and sadness during his short and tragic life. Because of the issue’s unique editing strategy, you experience Bobby’s life as if you are remembering Bobby’s life. Just as you experience Malick films, you experience Best Man Falls.

And by the time you see the panel of Bobby bleeding out on the floor, you understand:

Every death, no matter how significant, is an extinction of a small corner of history.